Your source for Arts & Entertainment content, as well as fabulous human-interest stories, from Baltimore and beyond!

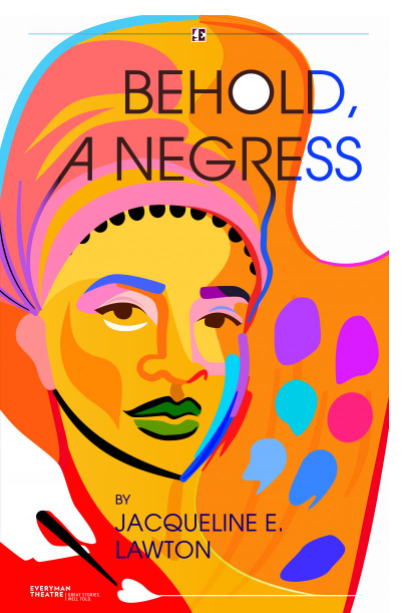

Everyman Theatre's 'Behold, A Negress' - An Interview with Playwright Jacqueline E. Lawton2/21/2022 By Frankie Kujawa Everyman Theatre’s Behold, A Negress, the World Premiere play by playwright Jacqueline E. Lawton, is a passionate and daring examination of the challenges of intersectional feminism and the role of art during times of social unrest and political upheaval. Running through Sunday, February 27th, the play is set in Paris at the beginning of Napoleon’s reign. With an imagined intimate relationship between real-life painter Marie-Guillemine Benoist and her muse Madeleine, a formerly enslaved black woman; both women maneuver the codes of women’s power in pursuit of their own liberty and equality. As the play unfolds, Marie’s ambition and desire for artistic recognition overshadow Madeleine’s sense of justice and personal integrity thereby causing the women to find themselves on the brink of their own revolution. Based on the playwright’s awestruck experience upon viewing with the real-life Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress) by Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Lawton discusses her inspiration for the play, the influences of her work, and what this experience has taught her about writing. Frankie Kujawa: What was your inspiration behind creating Behold, A Negress? Jacqueline E. Lawton: I love this question! So, first of all, I was inspired by the painting [Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist]. I believe it was in 2002 when I saw the painting. I was just struck and in awe by it. I was moved to tears by it. And the painting had been haunting me in this fascinating way of like, ‘There’s a story there. What is the story?’ I felt compelled to write about it. Then, in 2018, I learned about a grant that I could apply for which would support the development of three new plays. So, I applied for it. [These plays] were all centered on women. One play was looking at the impact of the #MeToo movement in the hotel industry, and that play was called Blackbirds. The next one was called The Inferior Sex, which is a behind-the-scenes look at a women’s magazine in 1972. Then it was this one – Behold, A Negress. So this was the same time when the #SayHerName hashtag and activist movement – it actually started before the hashtag really caught on – was trying to call greater attention to black, indigenous, Latinx women and gender non-conforming people who were killed at the hands of police and weren’t getting the same-level of attention or any attention at all. So, as that was happening, I was paying attention to the way that the bodies of women of color and black women, were used, abused, sexualized and manipulated without our control and our consent. At the center of my work, I like to place people of color, women of color, black women. For centuries, we did not know the name of the sitter - of the model - in this particular portrait. And, while at the same time I’m sitting around and thinking about writing this play, this great art historian named Denise Murrell [Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (2018)], had been actually trying to excavate the names of the black models in modern and classical art. And, she found Madeleine’s name! She had found her story. Literally, I had just finished writing the play and it was about to go into workshop. I read the article where the woman had discovered [the model's] name was Madeleine. So, I went back and changed the name of the character [in my play] to Madeleine. So all those things were literally happening at the same time. I was haunted by this painting; really wanting to explore the way that black women’s bodies were being used and what control we had, and then the discovery of this woman’s name. So, amazingly, it all came together for this play to exist. Frankie Kujawa: Now knowing Madeleine’s name, do you feel as if this play provided you a kinship to her spirit? By bringing this story to light, do you feel it shines a light on all those other models and figures who otherwise would go unnoticed and remain unknown? Jacqueline E. Lawton: I do. I love this question, and quite boldly, I hope so. It makes me feel like, ‘Ok, we now know Madeleine’s name; and this amazing historian found her name.' I don’t know [Murrell]. We had never been in contact. So, what I hope is that it encourages more artists like me and more playwrights and storytellers to bring forth the truth of these people’s lives to whatever extent that they are able. For me, I did a lot of research on sugar plantations, about the slave trade and French colonialism. So, I did as much research not knowing her specific history, but around her history to find out what kind of life she could have possibly had. And then what her life would have been like in the household of this aristocratic family. So, I hope that others who are out there, and want to tell these stories, will see that it’s possible and they’ll want to. I’m also hoping that other theatres will want to tell these stories, too. That’s what I hope! Frankie Kujawa: Did the portrait itself influence the time period in which you set this play in, or did you set this play in that time period for a specific reason? Jacqueline E. Lawton: When I learned about Marie [Guillemine Benoist] and her life, I found her very fascinating. She married rather late – she was 25 years-old. If you think about it, in the late 1700’s, women were getting married at 13, 14, 15-years old. She didn’t get married until she was 25, and she was really focused on her artistic career. So she clearly had a family that was a wealthy, prominent political family. They must have supported her in doing that. Mind you, there was a great deal of the Revolution happening, so not a whole lot of marriages were perhaps taking place. But, I find her very fascinating because she studied under these great masters, including Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Jacques-Louis David. She had to fight her way to being trained by them. And, so she was one of the few women to actually receive a residency at the Louvre. So this just speaks to her extraordinary talent, hard work and determination. So, I knew that I wanted to write [the play] around the time that it actually happened because we don’t have a whole lot of stories that are a looking at women, let alone black women, and what black women were doing to contribute to those ideas during that time period. So, I thought, ‘here are these two women, let’s just focus on the two of them.’ And we know, historically and accurately, that Marie was at the Louvre. The Portrait of Madeleine was exhibited there in 1800. In the beginning of the play, I lay all of these facts out there. But then there’s so much to imagine around what actually happened. I specifically told this story because I think of the Revolutionary plays, or even stories we have, are very male-centered or war-centered. And this makes sense in terms of what literally was happening in the moment. However, I just wanted to "turn the corner" and look and think, ‘Oh what are those people doing? What bold subversive choices were they making? Perhaps there’s a story there.’ So, that’s why I did specifically choose this time period. Frankie Kujawa: Why was it important for you to establish the romantic relationship between Marie and Madeleine in Behold, A Negress? Jacqueline E. Lawton: So, this [romance] is truly imagined, right, because I have no idea what kind of relationship they really had. I was not a fly on the wall (laughs). But a very intentional thing that I did was about 6 or 7 years ago, in my own writing, was I wanted to disrupt the heteronormativity that I was placing at the center of my work. I wanted to be more inclusive. Because if I say I’m an ally, an advocate or an accomplice in my work specifically where I’m working to disrupt white supremacy; I needed to disrupt the way I was coupling people in my plays. So, I’ve been doing a lot of extensive research about bringing in our same-sex couples, particularly our black lesbian couples. I want more of their stories to come forward. So what that means is I've been doing the research in a manner so that it’s not just my own work that I do, but it’s working in collaboration with people who share these identities. This is so I can really learn from them. I think one of the most important things when you’re writing across races, genders, sexualities, nationalities, etc. is that you’re working with collaborators who will tell you what works and doesn’t work. I make sure that I’m always working with people who are going to let me know where I’ve erred because of both not having lived the experience and/or the assumptions I’m making based on research and work I’ve done. Frankie Kujawa: In your opinion, what has the experience of writing this play taught you?

Jacqueline E. Lawton: Oh, wow! This question is really powerful. What I’ve learned is that nothing is done in isolation! While I was starting to write this play, we had Denise Murrell doing her extraordinary work of uncovering the name of Madeleine in regard to this painting. Again, we don’t know each other, and I’ve never met her, but both our individual work was tied by this painting. So those kinds of things happening are just meant to be. They’re part of that ‘kismet journey.’ All these things were meant to be. I also learned to have patience because sometimes we playwrights write these plays and no one ever picks them up because you don’t find the right community. But, someone eventually will. When Everyman Theatre read [the play] they fell in love with it. I found [Everyman Theatre] to be the exact right place for this play to launch. Baltimore is a great city, and Everyman does a beautiful job nurturing their artists. They also have such a great relationship with the high schools! Their education program is just fantastic! High school students got to see the play, and I was able to talk with them about the experience which was really beautiful. So, I think that trusting one’s instincts are very important, and knowing that there is an audience. People are really, really hungry to learn about the folks who are marginalized in society. And just because the stories haven’t been told before doesn’t mean that people don’t want them. For more information, please visit: everymantheatre.org/

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|